Battling The Mental Health Crisis Among The Underserved Through State Medicaid Reforms

February 11th, 2020 | viewpoint

This blog was originally posted on Health Affairs on February 10, 2020.

Total deaths from suicide, alcohol, or drugs, what some call “deaths of despair,” increased by 51 percent from 2005 to 2016 in the United States, and drug overdose deaths increased by 16 percent per year between 2014 and 2017. These statistics reflect the well-documented opioid crisis and what some experts have called a national “mental health crisis.” The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and related benefit parity requirements led to important strides in expanding behavioral health care coverage, but the law has not yet achieved its potential to advance full access to—and timely use of—behavioral health services.

The ACA was a milestone victory for behavioral health care access in two important ways. First, Medicaid expansion has been crucial to increasing access to mental health care and addiction treatment for previously uninsured, low-income adults. Approximately 29 percent of persons who have gained coverage through Medicaid expansion, or about five million people, have a mental or substance use disorder, or both. Having health insurance is a strong correlate of receiving mental health treatment: A national survey found that 75 percent of uninsured adults with mental illness and 56 percent of uninsured adults with serious mental illness did not receive treatment.

Second, the ACA improved behavioral health coverage by extending the scope of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 1996. The ACA broadened the applicability of MHPAEA by mandating that all plans, not just those that offered behavioral health benefits, provide coverage for behavioral health services by categorizing mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) services as an essential health benefit (EHB). Additionally, the ACA applied MHPAEA to Medicaid expansion by requiring that coverage offered through alternative benefit plans or Medicaid managed care plans comply with the EHB requirements and federal parity requirements. The extension of these parity requirements established minimum standards for behavioral health coverage that did not exist before the ACA.

While Medicaid expansion and the parity requirements related to the ACA represent important steps forward, much work remains to overcome the persistent challenges in access to MH/SUD care for individuals with behavioral health conditions. Implementation of Medicaid expansion and mental health parity requirements is left largely to the states; therefore, we believe states have an opportunity and an obligation to use multiple policy levers to improve the lives of individuals and families affected by unmet behavioral health needs. Based on our work with national and state behavioral health and primary care associations participating in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-funded Delta Center for a Thriving Safety Net, as well as interviews with more than a dozen national and state policy experts, we offer recommendations for states to advance access to high-quality behavioral health services within their Medicaid programs.

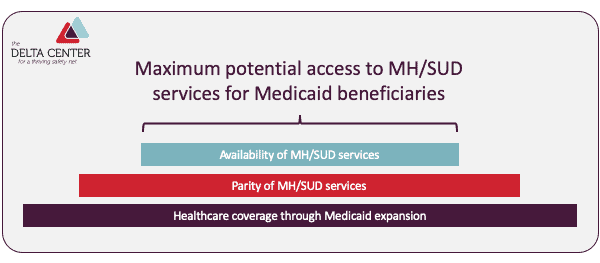

Realizing the potential of the ACA and benefits parity requires a three-fold approach: maximizing coverage through Medicaid expansion, ensuring full implementation of parity requirements, and addressing payment and workforce issues to increase the availability of mental health/SUD services. Exhibit 1 illustrates our conceptualization of how these approaches build on one another. We then describe how each of these factors contribute to expanded access.

Estimates suggest that if Medicaid were expanded in all states, an additional 1.5 million Americans living with MH/SUD would be eligible for coverage. Coverage gaps remain even in Medicaid expansion states, where about a quarter of uninsured nonelderly adults who are eligible for Medicaid remain unenrolled. This gap translates to an additional 8.8 million Americans without coverage for behavioral health services. Accessing coverage can be a challenge, as newly insured populations may lack awareness of enrollment procedures and the MH/SUD benefits available to them. Many vulnerable persons with MH/SUD conditions, particularly those with severe and persistent mental illness, are at risk of delaying or losing much needed treatment due to lapses in coverage or Medicaid churn.

Medicaid coverage serves as the foundation on which other efforts to expand access to behavioral health services can be built. Suggested approaches to increase Medicaid coverage include:

State laws and enforcement pertaining to parity within Medicaid expansion have varied in degree and approach. Of those states that have adopted policies or laws related to parity in Medicaid expansion, the majority have focused on parity by requiring Medicaid managed care organizations to comply with specific state requirements for the federal MHPAEA. However, these requirements often do not apply to coverage other than Medicaid managed care (such as Medicaid fee-for-service coverage). Most states also have not addressed non-quantitative treatment limitations on the scope or duration of benefits, such as separate deductibles and copayments for behavioral health and medical care and limits on behavioral health services offered within provider networks. Although this policy gap affects people with all coverage types, it has a disproportionate impact on underserved populations such as Medicaid beneficiaries. Finally, most states have not held Medicaid health plans accountable through strong enforcement of federal and state-related parity laws.

The effectiveness of MHPAEA depends on the scope of its implementation and degree of enforcement. Suggested approaches to expand and enforce parity include:

Reimbursement rates for behavioral health services are significantly lower than those for medical and surgical treatments, contributing to the lower network participation rates for behavioral health providers. For example, in New York State, community behavioral health organizations have been systematically paid an ambulatory patient groups (APG) rate, which has been below their cost of care. Furthermore, APG rates have not increased to reflect inflation for nearly a decade, leading to a widening gap between reimbursement and cost of care. In settings where behavioral health is integrated into primary care, there are often substantial differences between payment rates for primary care visits and behavioral health visits. For primary care clinic managers trying to maximize revenue, low reimbursement rates create a disincentive to expand and further invest in improved behavioral health services. The disparities in payment rates are even more pronounced between integrated settings such as community health centers and free-standing behavioral health clinics. For instance, in New Mexico, some non-health center behavioral health providers receive $50 for a visit, while health centers receive at least $172 for a comparable service.

The significant shortage and mal-distribution of behavioral health providers, especially in rural areas, also limits access. In 2016, there were approximately 31,180 licensed psychiatrists active in the US workforce, serving the estimated 44.7 million people with a diagnosed mental illness. These shortages are even more notable in state Medicaid programs, particularly in rural areas; on average, rural and frontier counties have 1.8 and 1.5 licensed behavioral health providers, respectively, per 1,000 Medicaid enrollees, compared with 6.4 in urban counties.

Compounding the issue of workforce shortages, state regulatory barriers prevent providers from operating within their full scope of practice. Restrictive scope-of-practice laws can prevent some health care professionals, such as advanced practice nurses and pharmacists, from prescribing medications or performing other important behavioral health services, even though they are trained and competent to do so. In addition, despite the evidence base for using peer counselors and community health workers to meet behavioral health care needs, many scope-of-practice laws limit their use in MH/SUD treatment and prohibit reimbursement.

Broader strategies to improve payment rates and workforce are needed to realize the vision of expanded MH/SUD access. Suggested approaches to increase availability of services include:

Despite the progress that has been made through the ACA and state implementation of Medicaid and mental health parity requirements, millions of Medicaid-eligible Americans with MH/SUD conditions still lack access to behavioral health services and suffer disproportionately in the nation’s mental health crisis, including the current opioid and suicide epidemics. States that already have expanded or are planning to expand Medicaid have the opportunity to better serve individuals with behavioral health needs by addressing the lack of coverage, parity, and availability of services. State policy makers should use all available policy levers to advance access and prevent the devastating and often tragic consequences that these unmet MH/SUD needs can have on the lives of individuals and families.

James Maxwell, Angel Bourgoin, and Zoe Lindfeld, Battling The Mental Health Crisis Among The Underserved Through State Medicaid Reforms, Health Affairs Blog, February 10, 2020, www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200205.346125/full/

Copyright © 2020 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.

We strive to build lasting relationships to produce better health outcomes for all.